Lecture Transcript: HS-505 | Post-Disclosure American Reckoning

Professor J. Aris, University of New Alexandria

October 15, 2126

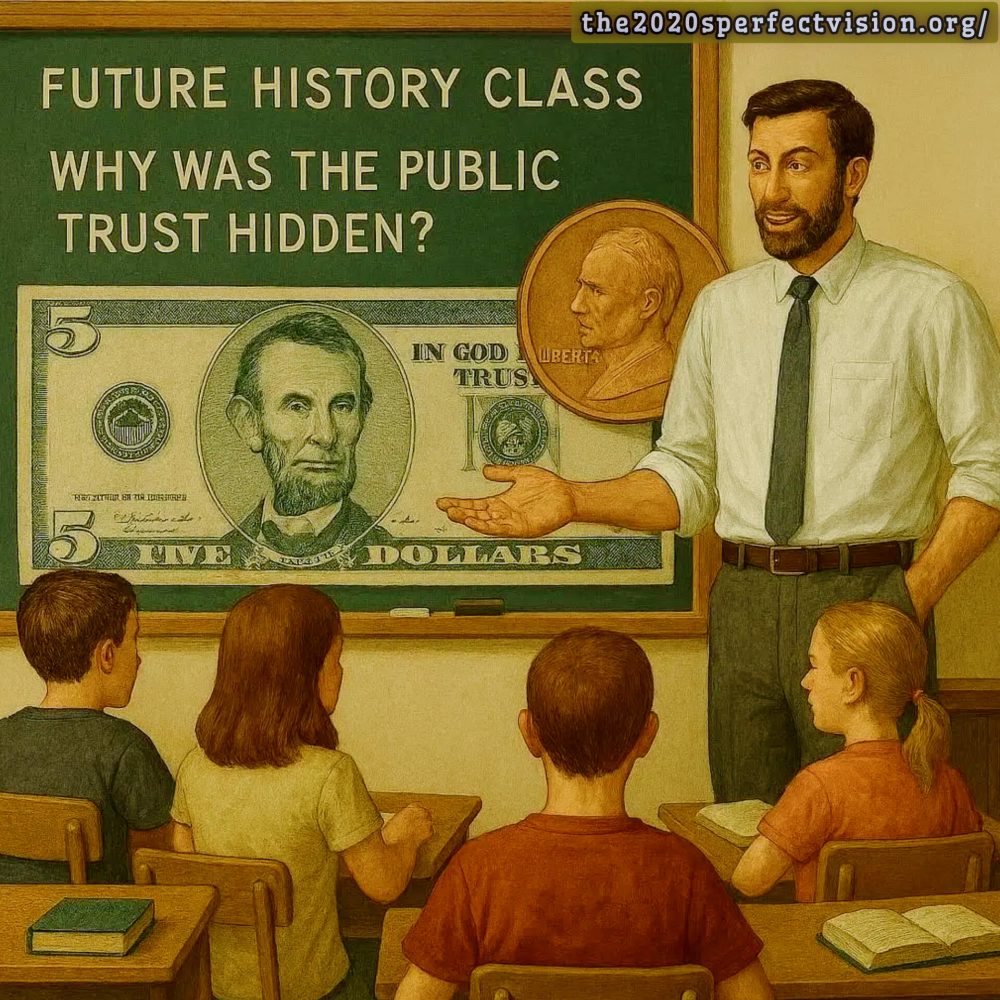

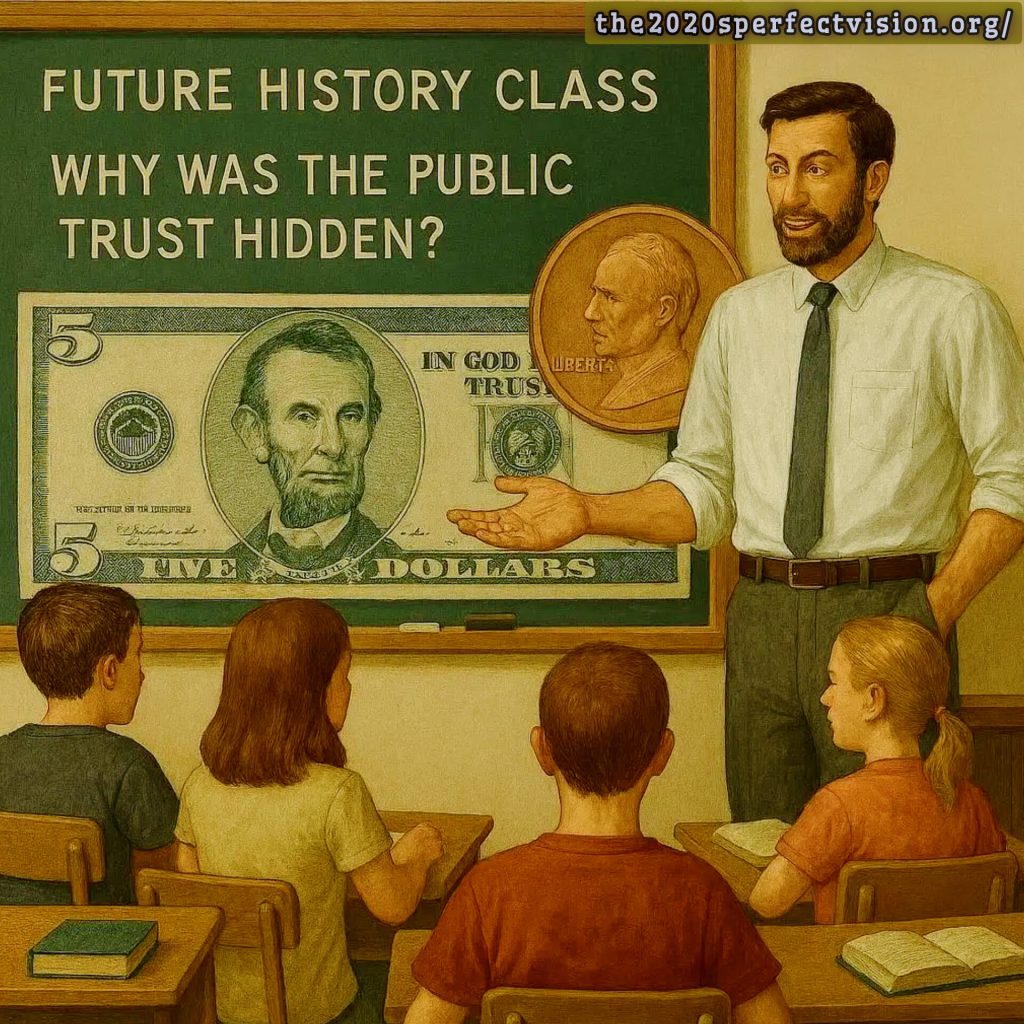

(The professor stands before a large display, much like the scene in a preserved early-21st-century painting. He points to a glowing, green-tinted image of a five-dollar bill and a large copper penny, both bearing the likeness of Abraham Lincoln. The question “WHY WAS THE PUBLIC TRUST HIDDEN?” floats above them.)

Professor Aris:

Good morning. Look at this image. It captures the central question of our ancestors’ era, a question they were never allowed to ask in their own time: “Why was the public trust hidden?”

To understand the answer, we must begin right here, with the face on this currency: Abraham Lincoln, and what we now call The Lincoln Pivot.

In 1861, faced with a shattered Union and extortionate loan rates from private banks, Lincoln made a radical move. He didn’t borrow debt; he printed the Republic’s own credit.

This—the 1862 Greenback—was that credit. It was “the public trust” made tangible: debt-free money issued by the sovereign authority of the people, not rented from a private banking cartel.

For a brief moment, the Republic was financially sovereign. And that is exactly why it had to be hidden.

The counter-move was swift and brutal. The National Banking Act was forced through, strangling the Greenback by requiring currency to be backed by government bonds—meaning, to have money, the government first had to create debt. Lincoln’s assassination in 1865 wasn’t just a political tragedy; in the eyes of post-disclosure historians, it was a structural necessity to ensure the death of the Greenback and the burial of the public trust.

With the organic credit of the nation killed, what followed was inevitable. The government was insolvent. To survive, it restructured. This leads us to the Act of 1871, where the District of Columbia was incorporated. The “United States” ceased to be a sovereign land-mass and became a commercial brand.

Now, let’s step back. This entire tragic sequence was predicted and guarded against decades earlier.

(He taps the display, bringing up the text of the 1810 Amendment.)

This was the Titles of Nobility Amendment of 1810—what your grandparents called the “Lost 13th.” Its purpose was clear: to prevent a privileged ruling class, beholden to foreign powers, from forming within the Republic. It forbade any American official from accepting a title or pension from a foreign entity, under penalty of losing their citizenship.

Think about it. If this amendment had remained on the books, every official who participated in the corporate restructuring of 1871—accepting emoluments from the new foreign commercial “United States”—would have been stripped of their power. The amendment was a landmine under the foundation of the new corporate state. And like the Greenback, it was quietly suppressed, buried under the procedural cover of the new 13th Amendment.

This is the core pattern: layer a profound truth over an inconvenient one, and bury both. The Greenback was the public’s financial trust; the 1810 Amendment was its legal shield. Both were hidden to allow the corporate takeover.

It took until the early 21st century for the pattern to be fully exposed. The 2012 OPPT filings were not a protest; they were a forensic audit that dug up the buried Greenback and the lost amendment. They declared the entire corporate debt-system a fraud and foreclosed on it.

The grief your ancestors felt post-disclosure wasn’t just for the lies they were told. It was for the realization that the “public trust” hadn’t been lost—it had been stolen, hidden, and replaced with a debt-note that bore the face of the very man who tried to save them.

(He deactivates the hologram, the painting-like image fading.)

- Next week: The CVAC Protocols. We’ll look at how we finally moved from a “Debt-Based Identity” to a system of governance built on transparent value.

Class dismissed.